Calcium Carbide treated mangoes, pesticidal spinach and toilet cleaner-ginger are just some of the modern day ghouls that haunt us today.

By Darshan Desai

Visit ORGANIC SHOP by Pure & Eco India

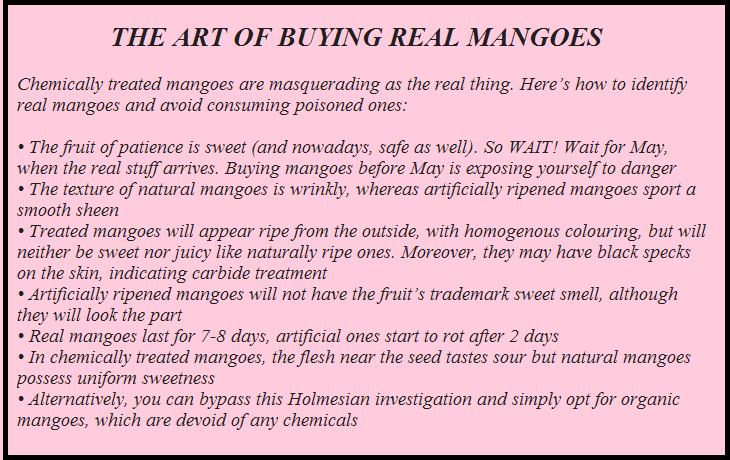

CALCIUM CARBIDE. Familiar with that name? Why, you have eaten it many times. Almost every summer, in fact. Remember you savouring mangoes in March and patting yourself on the back for being able to source ripe mangoes ahead of season? But those mangoes you consumed prematurely, in March, were most likely artificially ripened by deadly poisonous chemicals like calcium carbide (CaC2), which contains arsenic and is known to cause cancer. Carried away by your love for the national fruit, you likely did not notice the trademark sweet aroma of mango was missing or that it didn’t taste as sweet as ripe mangoes should, despite looking the part. You also did not notice that the mango’s shelf life concluded with two days, whereas, normally, mangoes last for up to 7 to 8 days.

Since you did not notice these things, let this author share the news flash with you that the above-described traits are common to mangoes poisoned with calcium carbide. The same calcium carbide whose original applications include making of acetylene gas, acetylene generation for carbide lamps; in chemicals for fertiliser, and in steelmaking. In other words, it is not meant for the tender interiors of the human body.

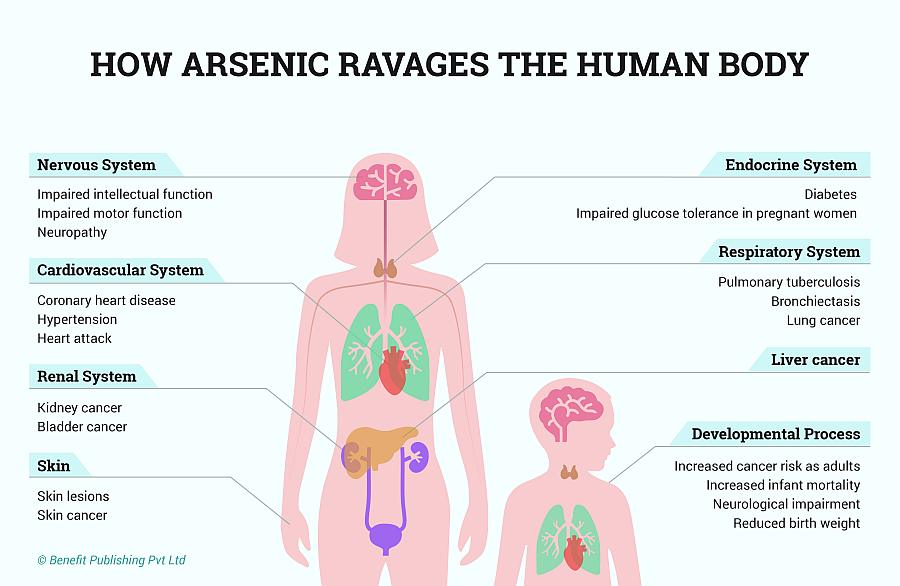

“Calcium carbide treatment of food is extremely hazardous because it contains traces of arsenic and phosphorous, and once dissolved in water, it produces acetylene gas. Calcium carbide is known to cause cancer and also causes food poisoning, gastric irritation and mouth ulcers, amongst other health problems,” says Mohammad Asif, Department of Pharmacy, GRD Institute of Management and Technology, Dehradun.

As per researchers of the Dhaka Medical College in Bangladesh, another country where mango treating is rampant, early symptoms of arsenic and phosphorus poisoning include vomiting, diarrhoea (with or without blood), burning sensation in the chest and abdomen, thirst, weakness, and difficulty in swallowing and speech. Other effects include numbness in the legs and hands, cold and damp skin and low blood pressure. In some cases, arsenic and phosphorus poisoning can prove to be fatal and prolonged consumption can lead to a host of cancers.

The artificial ripening often transpires at the point of sale, when the trader simply slips a sachet of calcium carbide (at a measly Rs 3!) or Masala as it’s called locally in the mango carton. Once the chemical is exposed to moisture it releases acetylene gas, which expedites the ripening of the mangoes. It takes just two days to convert the raw green fruit to a yellow market-ready, ripe one. Ready to masquerade as the real thing.

The use of calcium carbide in food is banned worldwide due to its hazardous effects on health but this practice continues with virtual impunity in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan and several other countries. In India, artificial ripening by calcium carbide is banned under the Prevention of Food Adulteration (PFA) Act, 1954, and the Prevention of Food Adulteration Rules, 1955. According to Section 44AA of the PFA Rules 1955, no person shall sell or offer or expose for sale or have in his premises for the purpose of sale under any description, fruits which have been artificially ripened by use of carbide.

Those convicted under this act could face imprisonment of up to three years. In fact, the Food Safety (Prohibition and Restriction in Sale) Regulations of 2011 provide for a fine of Rs 10 lac (approx $15,471) and imprisonment of up to two years for the crime.

Despite such laws, cases of traders or retailers being booked for artificially ripening fruits are virtually non existent. In Gujarat, which is a large producer of kesar and alphonso mangoes, the health wings of municipal corporations in Ahmedabad, Vadodara, Junagadh, Jamnagar, Surat, Rajkot and Bhavnagar and the inspectors of the Food and Drugs Control Administration (FDCA) recently swung into action and seized as much as 10,000 kg of mangoes ripened with calcium carbide from several local fruit markets. The huge quantity of the seizure is being attributed to strict orders by an activist Gujarat High Court, which took suo motu action based on reports of carbide ripening and ordered authorities to address the issue.

But those in the know don’t find this 10,000-kg statistic at all surprising or even impactful. “All this action is but a drop in the ocean—just an annual routine when some raids are conducted sporadically, some media grabs taken and that’s all. You are made to believe the administration is active,” shrugs Kapil Shah, founder of the non profit, Jatan Trust, which promotes organic farming and fosters rural communities.

“There is no rocket science at all. More than 70% of mangoes that come to the market before May 20 are all artificially ripened and generally, with calcium carbide. If authorities want, this can be prevented,” he says, with an air of implication.

Here’s the kicker: sources in the Gujarat FDCA confide that most of the action largely follows complaints or per force, and often involves “cooperation”. “Just as in the case of liquor, which is prohibited in Gujarat, some seizures are made in collaboration with traders to fulfil annual targets,” an official grins. Officials, however, insist the issue of carbide mangoes is not as straight as hauling up liquor. The Amdavad Municipal Corporation (AMC) claim to have seized and destroyed over 29,000 kg of calcium carbide treated mangoes over the last five years, but this figure is largely on the basis of complaints or surprise raids.

Officials state raids are the only way to detect artificial ripening since it is difficult for even laboratory tests to conclusively conclude the use of CaC2 in fruits. They point out that the acetylene gas released by calcium carbide—which induces artificial ripening—is a volatile gas, and its residue cannot be traced in the mangoes.

An FDCA official points out another problem on condition of anonymity, “It is difficult for us to follow the consignment of mangoes right from the farm to the market yard to the consumer. There should be awareness among consumers too, and they should desist from buying off season fruit.”

Disagreeing, the Gujarat Khedut Samaj’s (Gujarat Farmers’ Association’s) secretary, Sagar Rabari, says that most of the foul play occurs at the packing stage, rather than at the farm. “90% of the mangoes that come to the market before May are treated with CaC2 by traders at the selling point itself. Farmers are not involved,” he asserts.

Another dimension that further compounds the problem is that the vagaries of nature often leave the farmer—and so, the trader—with just about 15 days of “sale time”. “It has become a gamble; we get hardly 15 solid days to sell during the season. Sometimes the monsoon sets in early and sometimes unseasonal rain affects the crop,” says Ramesh Shiroya, assistant secretary at the Talala* APMC (Agricultural Produce Market Committee), who is also a farmer.

Market Yard Talala is a hub for the famous kesar mangoes of the Saurashtra region in western Gujarat. Climate change affects production, which is down by 35 percent in the region this season. Shiroya says his farm yielded 2,000 to 3,000 man (one man equals 20 kg) last season but “this time I could get only 450 man”.

Vaju Dobaria, another mango farmer from Talala, points out, “One tree, on an average, yields 300 to 400 kg, but now this has decreased to 30 to 40 kg. Last year, production was to the tune of 90 lac boxes, but it came down to 60 lac boxes this time.”

In a precarious scenario such as this, there is a tendency on the part of the farmer and the trader to cash in, in the little time they have. Artificial ripening by CaC2 comes handy at such times.

SPARKLY CLEAN INSIDES WITH HARPIC & SANIFRESH

While traders ripen mangoes using the poisonous calcium carbide, ginger farmers in south India have found an equally harmful out-of-the-box solution to ward off the deadly bacterial disease, rhizome (soft) rot, which kills the crop. Farmers from Wayanad and Idukki districts in north Kerala, discovered that Harpic and Sanifresh toilet cleaners fight the disease effectively.

The farmers mix a small quantum of the toilet cleaner in a bucket of 10 litres of water and then sprinkle this mixture around the roots of the crops affected by disease. The farmers, according to reports, received instant results—the method was both faster, as well as, more effective than conventional antibiotics like streptomycin and tetracycline.

However, following media reports, these farmers have become cagey. Deepa Sunny in Idukki simply told this writer that “we no longer deal in ginger”, while Jojee Joy of Highrange Traders, also in Idukki, wanted to know why this information was sought. Once informed, he said, “I am driving; I will call you back in an hour.” He never did.

Similarly, Vipin of Bea Business Limited, with farms in Wayanad and Kalpetta, said, “I will speak to you tomorrow.” All follow up calls to Vipin thereafter met termination within the first ring.

Even more worrying is that the potential health related repercussions of this newfound ‘solution’ are yet to be acknowledged by government agencies. Food safety officials say they deal only with harvested crops and are unaware of such a practice.

KILLER GREENS

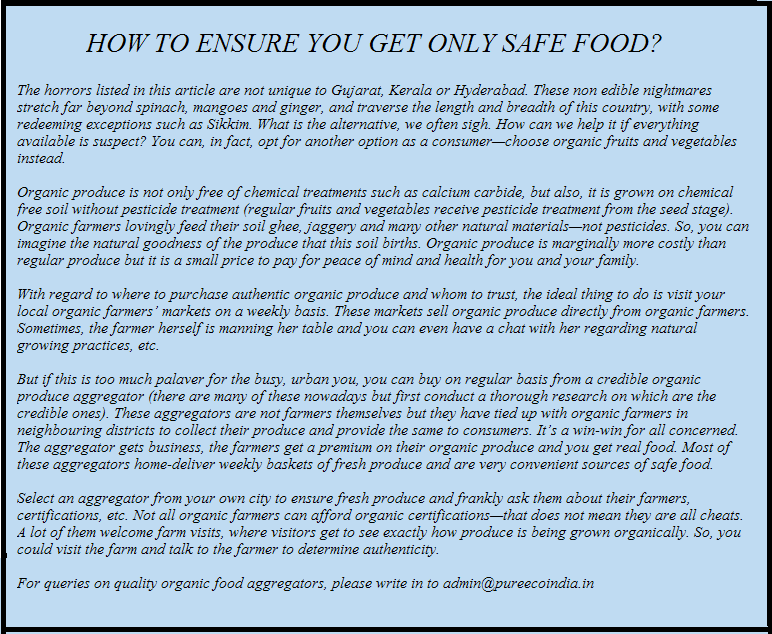

In 2016, a team of two researchers, G Geetha and C Sreenivas, from the Department of Entomology at Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University (PJTSAU), fanned across vegetable markets in Hyderabad to collect samples of spinach for study. They visited the three main vegetable markets of Hyderabad—Gudimalkapur, Mehdipatnam and Shamshabad. Upon testing the samples, the duo found the leafy green vegetable laced with as many as 11 pesticides—five of which were common to all samples.

Despite the alarming results, they are unable to give a number to the exact amount of pesticide residue that poses a health risk since authorities have not yet decided on a Maximum Residue Limit (MRL) for spinach. The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) has set MRL standards only for a few vegetables such as soybean, onion, ginger, okra and green chillies, which are exported.

However, Dr Shashi Bhushan Vemuri, former head of All India Network Project on Pesticide Residues, opines residue or no residue, “pesticides should not be on spinach at all”.

In fact, any amount of pesticide residue would be harmful. The word ‘Cide’ in ‘Pesticide’ originates from the eponymous French word meaning ‘Killer’, and the Latin word, ‘Cidium’, meaning, ‘A killing’. As the name suggests, it is made to kill.

______________________________________________

*Talala: Talala is a taluka in the Gir Somnath district of Gujarat

Leave a Reply